A few weeks ago I harvested a small number of Müller-Thurgau grapes, pressed them, and clarified and fermented the juice. The question then was to leave it as is, or to go through a second fermentation and make sparkling wine. In the spirit of experimentation and education, I chose to make bubbly!

In order to add the bubbles naturally (versus making a secco where carbon dioxide is simply added to wine), a second round of yeast and sugar is added to the wine, and the bottles are then capped and cellared to be left on the yeast.

Prior to fermentation, the juice had 77ºOechsle (total sugars), which equates to an expected alcohol level of about 10.3%. Using the handy dandy table below, we can see that this means there is 81g of alcohol/L. When making sparkling wine, one can legally add only 1.5% alcohol. 10.3 + 1.5 = 11.8. This means we are enriching just under 12g of total alcohol with sugar for this second fermentation. We must therefore add 2.93kg/100L, or 0.0293kg/1L of sugar to the wine.

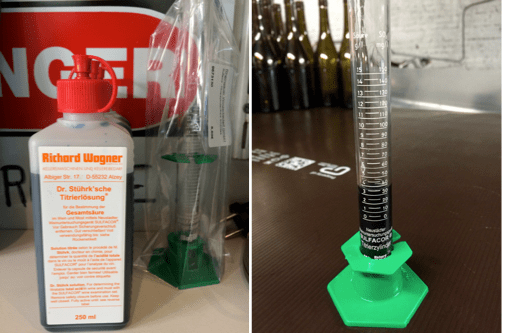

We had 17.5L of wine, so 0.0293kg x 17.5L = 0.512kg. Grams are easier to work with, so 0.512 x 1000 = 512g of sugar needed to be added the 17.5L of wine.

A strain of Sekt yeast was also then added. The rule for this yeast was 20g yeast/100L liquid, or 0.2g/L/1L x 17.5L of wine = 3.5g yeast to be added.

Another thing to note is that the newly fermented wine was stinky. That’s right, really, really stinky. This is a common problem with wine and occurs when the yeast doesn’t have enough sugar to eat. When this happens, the yeast starts eating amino acids – some of which contain sulfur – and produces this farty smell. The way to combat this during the fermentation process is to add nutrients for the yeast to eat. We had done this, but alas we had really hungry yeast. After fermentation, the way to correct this smell is through aeration and copper. We did this and also again added additional nutrients.

The next step is to bottle and cap the soon-to-be Sekt. The bottles must first be sterilized. To do this, a sulfur-water solution is sprayed into the bottles. The bottles are then 95% filled with the wine and sealed with a bottle cap.

Sparkling wine bottles are thicker and stronger than standard wine bottles in order to hold up to the carbon dioxide pressure. Even with these specially designed bottles, you can only have 7.5 bars of pressure within the bottle. Doing our due diligence, we checked this. You get 0.47g of CO2/1g fermentable sugar (and 0.46g alcohol). We had added 512g of sugar. 512g x 17.5L = 29.25. 29.25 x 0.47 = 13.75g CO2. Using a specific table, this equaled exactly 7.5 bars of pressures. Phew!

Finally, the bottles are placed on their sides in a cool, dark place. The amount of time the now sparkling wine remains aging on the yeast cells differs according to country, quality level, and desired flavours. For this experimental wine we plan on only waiting for a minimum of 3 months. With this 3 month wait-time, in December the spent yeast cells will be removed through a process called degorgement, corks inserted, and I will be able to cheers to the new year with my very own bubbly!