Why Prune?

One of the first rules of grape growing is: struggle = reward. This is why artificially watering vines, even in times of drought, is generally disproved of (or illegal) in order to make sure the roots grow deep and strong and lead to more resilient vines. When it comes to the production of grape clusters, you want to aggressively prune branches in order to condense the available nutrients into each grape berry. Too many grapes fighting over limited nutrients a great wine does not make. You need to keep the quantity low and quality high.

In fact, quality designations in wine are partially derived from the amount of grapes picked from vineyards. Each country has it’s own regulation. For example, in France the AOC regulates the allowed yields. In Germany’s VDP classifications, the basic “classic” wines can be harvested at a yield of 100 hectare litres/ hectare; after that it drops drastically to 60hl/ha for all other succeeding “selection” quality designations. In addition to protecting the consumer by regulating quality, this also helps avoid more overproduction in an already saturated market.

In the first months of the new year, when the vines are dormant, you select which vine branches will be kept to produce that year’s grapes. Branches that are too new, or grow spontaneously from the bottom of the trunk, lack genetic information that tells them how to grow grapes. Keeping old vines means an unruly, unmanageable trellis with too many grapes and branches fighting for a limited energy supply.

How to Prune

Cane Pruned vs. Spur Pruned Vines

There exist two different methods to prune grape vines: cane pruning and spur pruning. The decision on pruning style depends on the quality of the branch-growths available, and then how you train the branches to grow (though certain pruning styles are more effective for certain grapes varieties).

First: Instructions on How to Prune

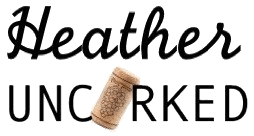

For cane pruned vines, as a basic rule of thumb, you count from 1 to 3 to understand which branches to keep and which to cut. 1=last year’s branch that will grow this year’s shoots and grapes; 2=branch from 2 years ago; and 3=the head – in old vines the gnarly looking nub that is connected by 2 or 3 years to the original trunk that gets larger and larger with pruning.

The “Head” of the Cane System

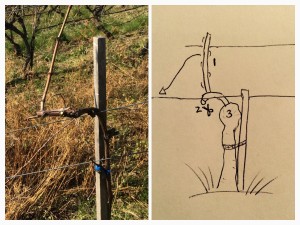

By cutting the 2-branch at the point just after the 1-branch, you are keeping the branch that will grow this year’s grapes as close to the trunk, and therefore energy supply, as possible. The 1-branch gets bent around the bottom metal trellis wire (like the 2-branch as seen in the photo below) and then grows new shoots up towards the sun and sprout grape clusters.

Officially speaking, for this year’s growth the 1-branch is called the cane, the 2-branch the arm, and the 3-branch the head.

The 1-2-3 Method of Cane Pruning

With spur pruning, a long, thick, semi-permanent branch called the cordon grows horizontal along the trellis wire from the trunk. From the cordon, spurs grow up and produce the grape shoots. With pruning, you are essentially giving dormant canes a hair cut and they are now called spurs. This method is simpler to understand and execute.

Spur Pruning a Cordon System

Learning Curve

On Saturday, in sunny 7ºC weather, I, along with members of Garage Winery’s vine sponsorship community, met on the hills of Rüdesheim above the Rhein River to learn about pruning and try our hand at the process. It is quite upsetting to see such large pieces of healthy vines be cut. It takes some time to come to terms with the fact that the branches grow back during the season and that this truly is the best way to keep the grapes as healthy and flavour-packed as possible. After all, wines are the result of not only the wine making process, but of decisions made to the raw material in the vineyards. So go ahead and prune those vines. No pressure.